A man does want some privacy, if you please. But he doesn't want too much. Alright, if we all knew what we said about each other, there would not be four friends in the world (Pascal). If we all knew what we thought, there would not be two. And 'if God proclaimed the secrets of men, the world could not endure' (Lichtenberg). But suppose nobody knew what anybody said or thought (or anywise experienced), not because they didn't (factually) but because they couldn't (logically)—that would be worst of all. Solitary confinement is a punishment, don't let's forget, even a torture.

A man does want some privacy, if you please. But he doesn't want too much. Alright, if we all knew what we said about each other, there would not be four friends in the world (Pascal). If we all knew what we thought, there would not be two. And 'if God proclaimed the secrets of men, the world could not endure' (Lichtenberg). But suppose nobody knew what anybody said or thought (or anywise experienced), not because they didn't (factually) but because they couldn't (logically)—that would be worst of all. Solitary confinement is a punishment, don't let's forget, even a torture.How lamentable, then, that humankind has been in extreme solitary confinement for four hundred years! Who did this to us? The early modern philosophers. How? It comes to this. They concretised abstractions and they literalised metaphors, turning (as such) rightful methods and locutions into wrongful metaphysics, giving us two logically-isomorphic (although epistemically-dimorphic) worlds: here a private world of unshareable intramental objects, there a public world of shareable extramental objects.

Ex hypothesi, psychological experiences (e.g. sensations) are object-relata over which the subject-referent has exclusive ownership. Such relata are immediately accessible to inlookers, but only mediately accessible to onlookers, if accessible at all. We know infallibly that we ourselves are experiencing such-and-such, but that others are so experiencing we know fallibly, if we know at all. Moreover, separate experiencers cannot have the same experiences, leastwise not numerically. Thus A.J. Ayer: 'It would be a contradiction to speak of the feelings of two different people as being numerically the same; it is logically impossible that one person should literally feel another's pain' (Problem of Knowledge, p. 202).

[Side-note: This seventeenth-century manor, originally built by Descartes & Co., has by now been severally refurbished. (The British empiricists, for example, changed the locks and repainted.) But it still stands as the building in which most philosophers and scientists are metaphysically tenanted, especially such as write books called Descartes' Error (wherein, as our Galen Strawson says, they super-erroneously out-Descartes Descartes).]

|

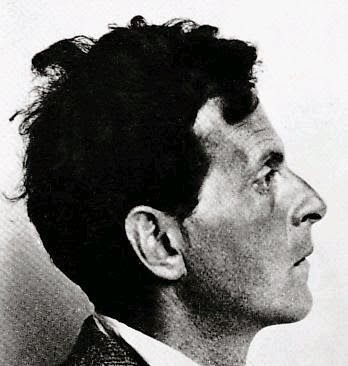

| Wittgenstein (uncombed) |

'There are propositions of which we may say that they describe facts in the material world ... There are on the other hand propositions describing personal experiences ... At first sight it may appear [...] that here we have two kinds of worlds, worlds built of different materials: a mental world and a physical world. The mental world in fact is liable to be imagined as gaseous, or rather, aethereal. But let me remind you here of the queer role which the gaseous and the aethereal play in philosophy—when we perceive that a substantive is not used as what in general we should call the name of an object, and when therefore we can't help saying to ourselves that it is the name of an aethereal object.' (Blue and Brown Books, pp. 46-7; cf. Zettel §482).But an experience isn't an object. 'It's not a Something, but not a Nothing either!' (PI, §304). To objectify an experience is to concretise an abstraction. And such objectification is problematic for theorists, insomuch as there isn't an exact symmetry between the logic of objects and that of experiences. If experiences were objects then it would be alright to say that we have access to them. But they aren't, and we don't. (To be in pain, say, isn't literally to have access to anything, neither directly nor indirectly.) If a pain were an object, an intramental object-relatum, then it would be alright to say, 'Logically, you can't have my pain.' But it isn't, and it isn't.

' "Another person can't have my pains." My pains—what pains are they? What counts as a criterion of identity here? Consider what makes it possible in the case of physical objects to speak of "two exactly the same": for example, to say, "This chair is not the one you saw here yesterday, but it is exactly the same as it."We can experience the very same experiences—Deus gratia—feel the same feelings, believe the same beliefs, enjoy the same pleasures, endure the same pains, and so on. Note that although objective sameness is numerical or qualitative, experiential sameness is neither. (Compare chromatic sameness. Suppose two men had matching pocket-squares of red. Would it be right for them to say to each other, 'YOU can't have THIS red'? [Cf. BB, p. 55.])

In so far as it makes sense to say that my pain is the same as his, it is also possible for us both to have the same pain. (And it would also be conceivable that two people feel pain in the same, not just the corresponding, place. That might be the case with Siamese twins, for instance.)

I have seen a person in a discussion on this subject strike himself on the breast and say: "But surely another person can't have THIS pain!" The answer to this is that one does not define a criterion of identity by emphatically enunciating the world "this." ' (PI, §253).

What of the epistemic-privacy worry, that we can't really know what anybody else is (e.g.) thinking? Wittgenstein stands that on its head: 'I can know what someone else is thinking, not what I am thinking' (Philosophy of Psychology, §315).

'In what sense are my sensations private? "Well, only I can know whether I am really in pain; another person can only surmise it." In one way this is false, and in another nonsense. If we are using the word "know" as it is normally used (and how else are we to use it?), then other people very often know if I'm in pain. "Yes, but all the same, not with the certainty with which I know it myself!" It can't be said of me at all (except perhaps as a joke) that I know I'm in pain. What is it supposed to mean, except perhaps that I am in pain?' (PI, §246).See, 'one says "I know" where one can also say "I believe" or "I suppose" ' (PP, §311). 'Doubting and non-doubting behaviour: There is the first only if there is the second.' (On Certainty, §354). Thus, where it makes sense to speak of knowing, it also makes sense to speak of not knowing—and here it does not. Where certain knowledge is intelligible, uncertain acquaintance and outright ignorance are also intelligible—and here they are not. (Consider 'I don't know if I'm in pain, let me check,' 'I believed I was in severe pain, but I was mistaken,' etc.)

'Someone who remonstrates with me that one sometimes does say "But I must know if I am in pain!", "Only you can know what you feel," and similar things, should consider the occasion and purpose of these phrases. "War is war" is not an example of the law of identity, either.' (PP, §311).

'When you say, "I grant you that you can't know when A has a pain, you can only conjecture it," you don't see the difficulty which lies in the different uses of the words "conjecturing" and "knowing." What sort of impossibility were you referring to when you said that you couldn't know? Weren't you thinking of a case analogous to that when one couldn't know whether the other man had a gold tooth in his mouth because he had his mouth shut? Here what you didn't know you could nevertheless imagine knowing; it made sense to say that you saw that tooth although you didn't see it; or rather it makes sense to say that you don't see his tooth and therefore it also makes sense to say that you do. When on the other hand, you granted me that a man can't know whether the other person has pain, you do not wish to say that as a matter fact people didn't know, but that it made no sense to say that they knew (and therefore no sense to say that they don't know). If therefore in this case you use the term "conjecture" or "believe," you don't use it as opposed to "know." That is, you did not state that knowing was a goal which you could not reach, and that you have to be contented with conjecturing; rather, there is no goal in this game.' (BB, pp. 53-4).

To be continued.